Today, in early 2018, the Legible London (LL) city wayfinding system includes over 1,500 individual pedestrian wayfinding signs – the iconic double-sided totems placed around town centres, outside rail stations, and along canal towpaths all across the UK’s capital. The maps found on all of these signs are born out of the Legible London mapping database (LLDB); designed, built and maintained by T-Kartor on behalf of Transport for London (TfL).

However, back in the middle of 2010, the fledgling LLDB covered only a section of central London – specifically the zone for the first phase of Cycle Hire that would launch that summer. TfL had received a warm response to LL pilot studies around Bond Street and South Bank, and held ambitious plans to build on this initial success and launch LL maps in every part of London. This would entail not just the installation of many more sign-based schemes, but also see paper-printed local area maps posted at Tube and DLR stations, bus stops, tram stops, and National Rail stations throughout TfL’s jurisdiction. Add in the extra attention London was expecting to receive less than two years later while hosting the London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games, and the pressure to rapidly grow the LLDB was very much on.

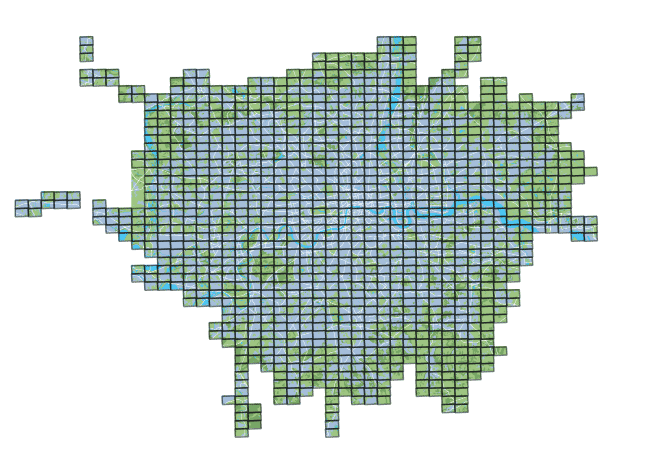

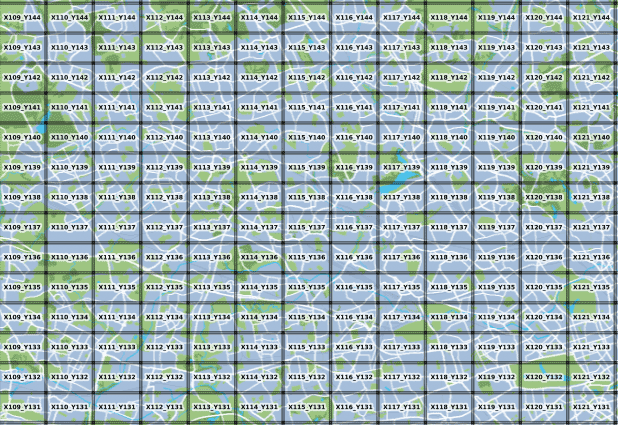

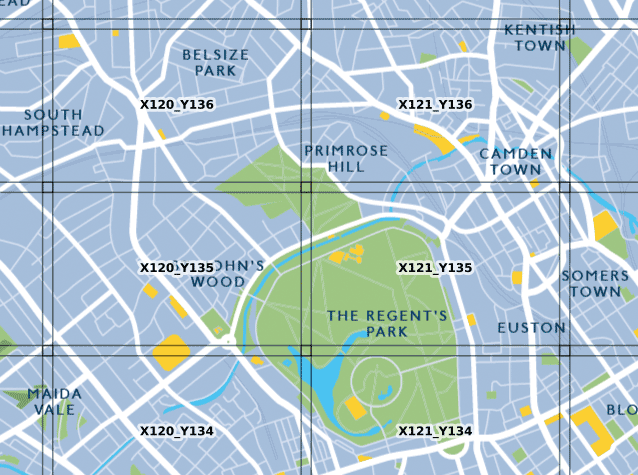

It would be stating the obvious to say that London is a big place; the expanse covered by all 32 boroughs and the City of London itself runs to almost 1,600km2. Bigger still is the area TfL actually cares about, namely where fare-paying passengers make use of TfL services each day. The London Underground reaches out into Buckinghamshire, Hertfordshire and Essex, and London Buses services regularly call at stops in locations nobody would consider as being within the capital itself. TfL has the same responsibility to provide information to its customers out here, as it does within London proper, and this includes local area maps to help customers (in TfL’s own words) “continue their journey”.

So the full expanse to map ‘legibly’ was actually London + a bit more. As a starting point, T-Kartor and TfL agreed to make use of perhaps the most authoritative topographic data source available – Ordnance Survey’s MasterMap (OSMM). However, to be able to produce mapping to LL’s graphic spec, further data sources were used. This included GeoInformation Group’s UKMap product, to assist with land use categorisation, and to source light-controlled pedestrian crossings, thus allowing people to better plan their walking route.

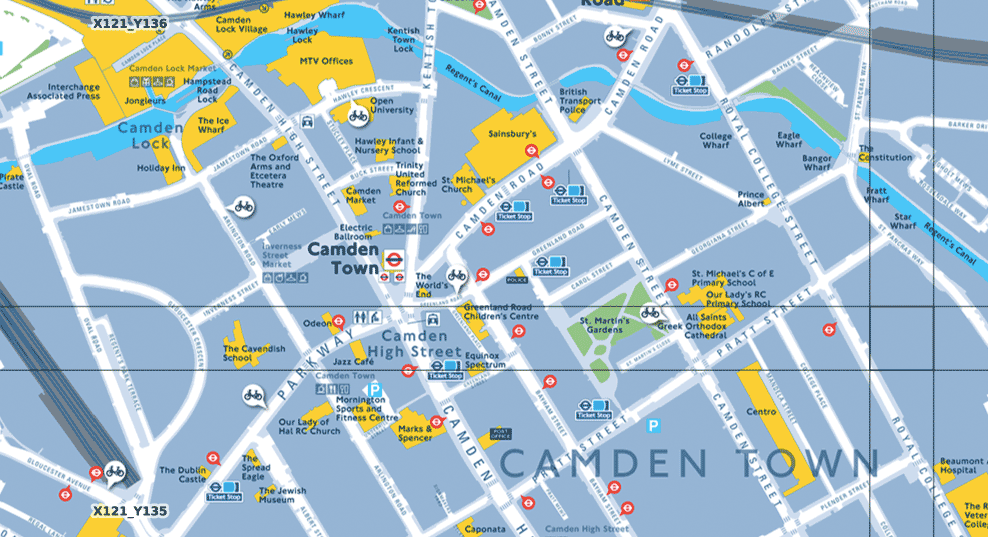

Relying on third-party data alone still wasn’t enough for Legible London though. TfL wanted LL mapping to achieve even higher levels of accuracy and currency, and to this end they included in T-Kartor’s commission the requirement to field check every ‘landmark building’ destined for use by the LLDB. Landmarks are a central pillar of LL’s philosophy, shown on maps as strikingly bright yellow polygons against dark background layers, and the definition of what is and what isn’t a LL landmark extends far beyond the obvious idea of a place tourists would be happy to be photographed at. In the ‘Legible’ sense, a landmark building is any such that may be useful for pedestrian wayfinding. It needs to be obvious, memorable, located on or very near to a pedestrian route, and ideally have a large, clear sign with its name displayed.

That last criteria drove much of the workload for T-Kartor’s field check teams, as they would carefully transcribe the exact building name used in the real world for use in the LLDB. The mantra was “the building name on the map should match the name on the sign”. Correspond exactly, without exception. And while this did result in a known “inconsistency” in building naming (for example, ’Saint’ in full or ‘St’ in abbreviated form? The sign on the street decides!), not to mention angst-filled internal squabbles for a field checker unlucky enough to discover a mis-spelt building sign, it did allow for the LLDB to very accurately map the situation on the ground.

Trusted third-party data, mixed in with very thorough in-the-field checking. The LLDB stove pot was starting to simmer nicely. The recipe wasn’t complete yet though. TfL also took the pragmatic step of inviting comment as to the content of the LL basemap from a number of their stakeholders. Chief among these were local planning and transport officers at each of London’s 32 boroughs, TfL fully aware that wilful adoption of LL wayfinding signs on borough-managed streets would be more likely if (almost) everyone agreed with what was actually shown the maps themselves.

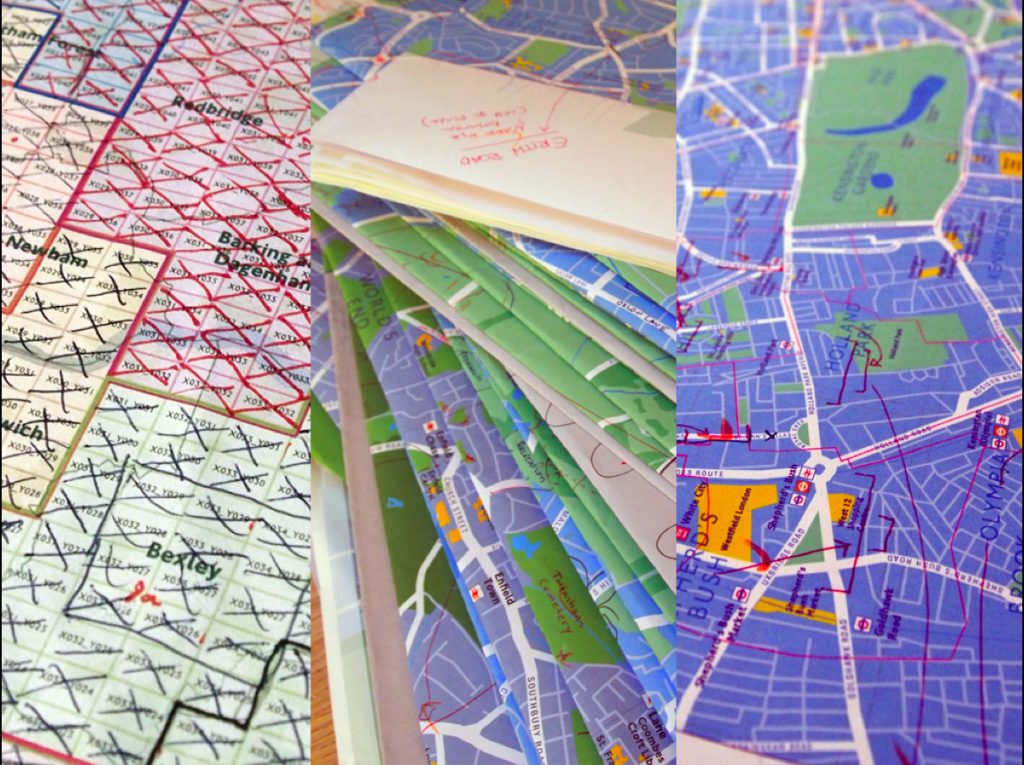

And this is when the LLDB creation process was kept decidedly old-school. Large format map proofs were printed off the plotters at TfL HQ in Victoria, bundled up into borough-by-borough rolls, and then walked, bussed, trained or cycled over to each borough’s planning office. A few “rules of proofing” were laid down – ”please don’t worry too much why Sainsbury’s is shown but Tesco’s isn’t”, “ yes, do tell us if you know that road junction is going to be drastically remodelled in the next six months” – and then the printed proofs were left with the borough teams to hang on the wall with a large pack of marker pens left invitingly close-by. A week or so later, the plot proofs were gathered back together, scribbled markings, notes and diagrams discussed and clarified, and then fed back to the mapping database builders at T-Kartor.

Smaller boroughs such as Hammersmith & Fulham could be covered in a single session, but their larger cousins Bromley, Kingston and Hillingdon often required multiple visits. And the breadth of comments was surprisingly wide, and genuinely insightful – particularly when it came to gaining knowledge of near-future developments and changes to the public realm that, if missed, would have rendered maps out of date almost as soon as they went on-street. In total, over 8,000 comments were made by stakeholders during the course of the LLDB build, with every single one considered, verified or dismissed. Examples of the latter were thankfully not too numerous, though it paid off to treat with subtle scepticism requests for inclusion of every pub in that particular borough – especially if those comments were put forward by a thirsty-looking borough planning officer on a sunny Friday afternoon…

The success of the stakeholder engagement tranche of Legible London’s database project really came down to two factors. Firstly, every single comment by the 100s of surveyed stakeholders was funnelled through just two gatekeepers – one at TfL, and one at T-Kartor. This allowed for a consistent policy in accepting and rejecting feedback to be employed. Secondly, it is perhaps impossible to underestimate just how much people love looking at maps. This may be a truism applicable to any map, to a degree, but is especially so to those as clear and as detailed the ones produced to LL specification. And when offered the opportunity to influence the what ends up on the map? Even harder to resist!