Imageability: that quality in a physical object which gives it a high probability of evoking a strong image in any given observer. It is that shape, color, or arrangement which facilitates the making of vividly identified, powerfully structured, highly useful mental images of the environment – Kevin A. Lynch, “The Image of the City” (1960)

Today, Kevin A. Lynch is revered as a godfather of modern city wayfinding. An urban planner and a scholar, Lynch’s most influential work dates back to 1960 and a five-year study of the ways in which people imagine, perceive, map and recall a city landscape.

Lynch’s thrust was to underline how the legibility and character of an urban environment feeds into the creation of mental maps in somebody navigating the city terrain. He studied the experiences of people in three US cities; Boston, Jersey City and Los Angeles. Lynch asked participants to sketch out and describe in detail numerous trips through the city, and came to the conclusion that we make sense of our surroundings in predictable and consistent ways.

A legible city, Lynch argued, was one that utilised patterns of recognisable symbols, those that are at once easily identifiable and grouped logically. Lynch defined the elements that make up these symbols as paths, edges, districts, nodes and landmarks.

These same five elements still play a foundational role in the design of modern city wayfinding systems. Perhaps the world’s largest City Wayfinding system is Legible London, a high profile example with lineage in theories and best practice refined over the half-century since Lynch’s seminal work. And as we shall now see, Legible London is just one of a growing number of wayfinding schemes that continue to prove his thesis.

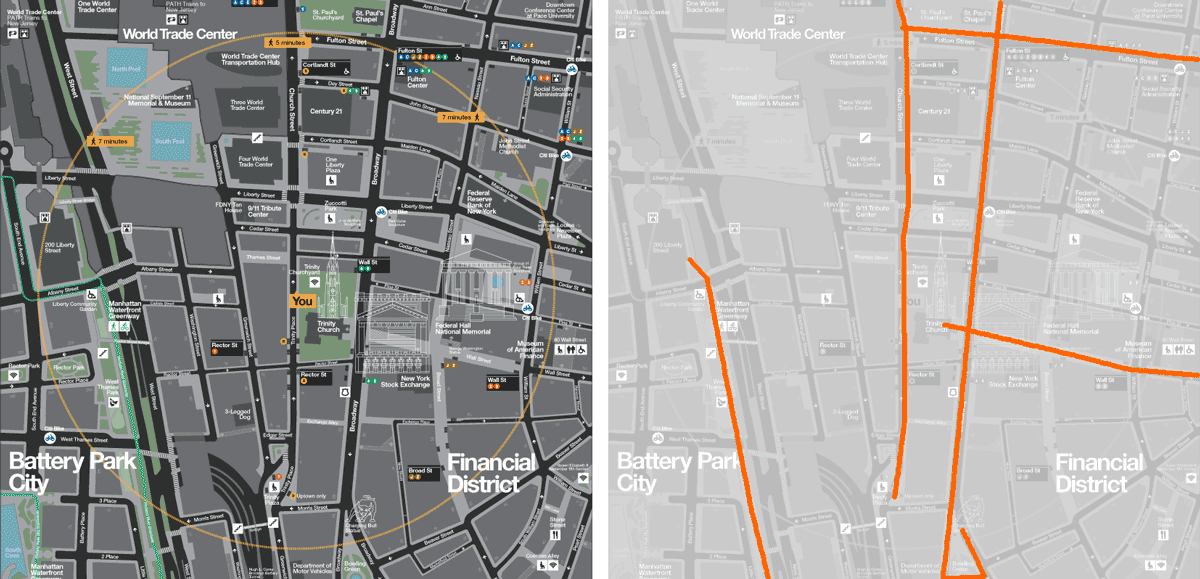

WalkNYC – New York City wayfinding

A path in the Lynchian-sense is any route or channel along which somebody travels. Prominent, legible paths are those that lend character, and might include a concentration of specific activity or distinct facade along a street. They may follow an edge (see below) or other topographic feature. Paths should be easily identifiable, have continuity and a functional necessity. Good city wayfinding design uses paths as prominent features on a map, as in the above example from WalkNYC in New York City.

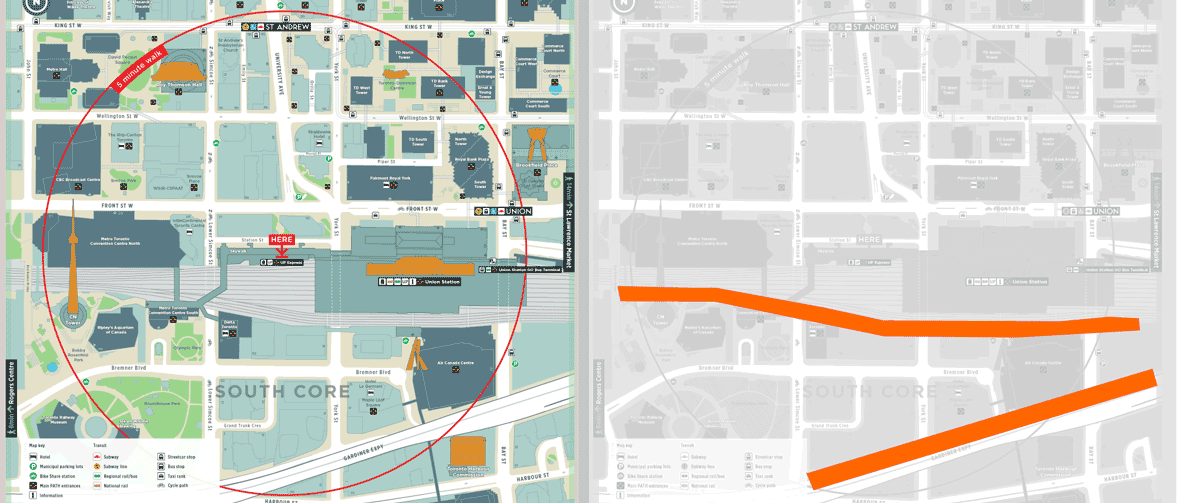

TO 360 – Toronto wayfinding

Edges are boundaries between distinct areas: examples in the city landscape may include roads, parks, shopping districts and residential areas; or natural barriers such as water and green spaces. Edges are linear, though do not qualify as paths. The wayfinding design above, from TO360 in the City of Toronto, defines edges along a railway line and major road.

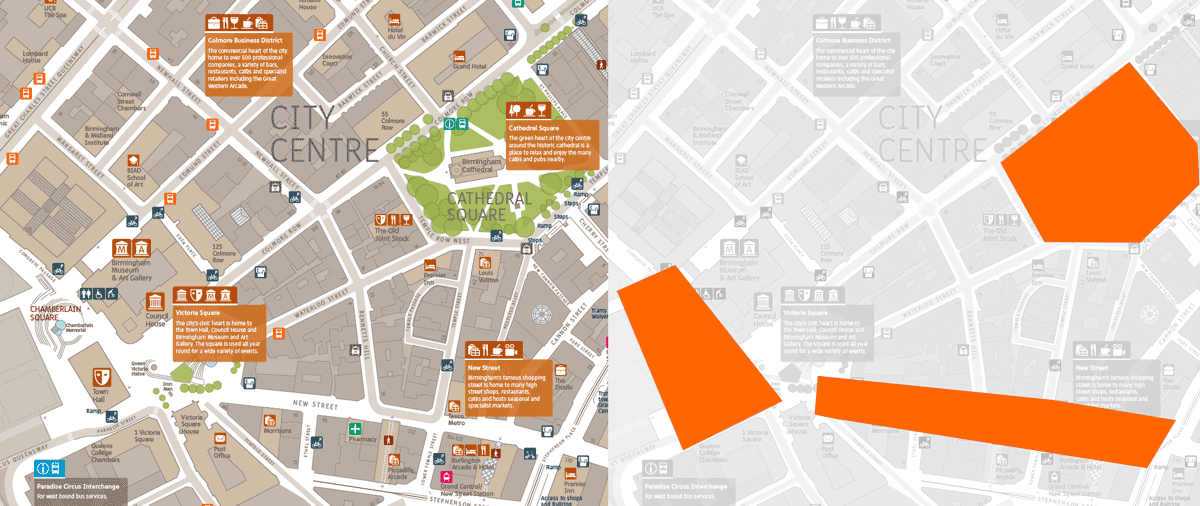

Interconnect West Midlands – Birmingham UK wayfinding

A district is a relatively large city area with a common character, one which the observer can easily categorise. It has a homogenous character, taken from its use or function, texture, space, form, building types, inhabitants or typography. Wayfinding maps can define and lift districts graphically, or by using naming styles and conventions, as in this example from Interconnect West Midlands (Birmingham, UK).

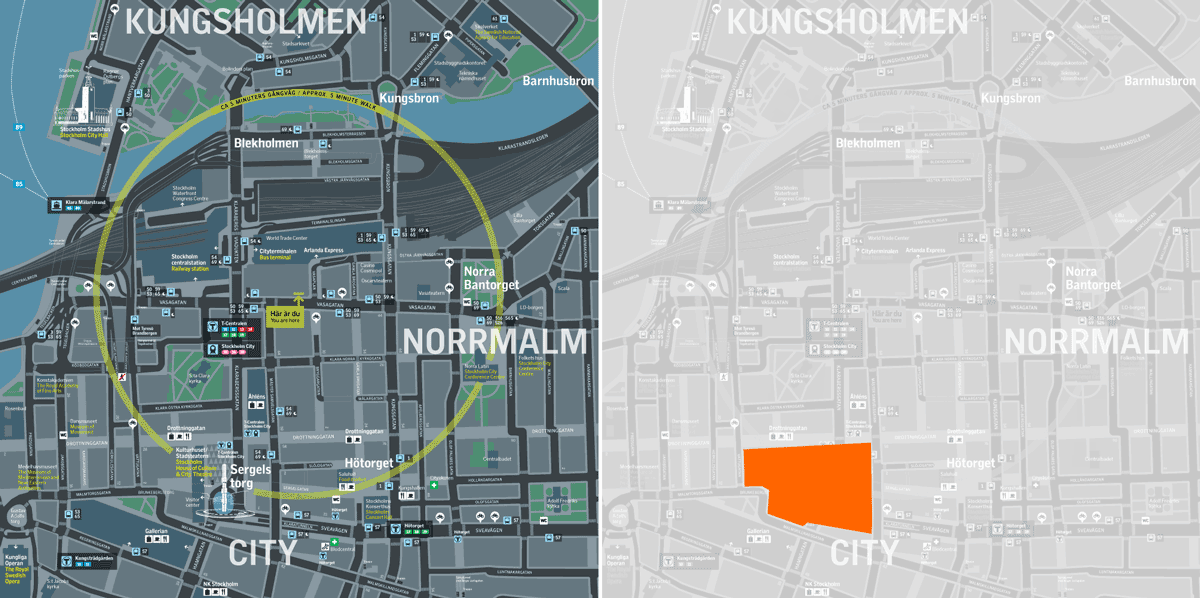

Stockholm Regional Transport (SL) wayfinding

A node is a focus point, and highly compelling to the navigator. Squares, junctions and access to transport are examples of nodes. Paths that cross can be nodes, though too many could render them undistinguishable. A node can also be a thematic concentration, such as a commercial street corner. Nodes, as well as areas of distinct public realm, are emphasised on this map for Stockholm Regional Transport by adding extra detail to these areas.

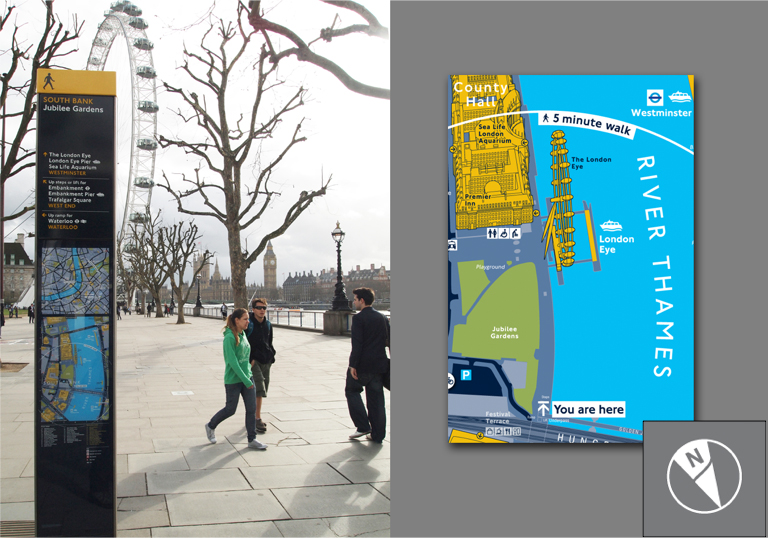

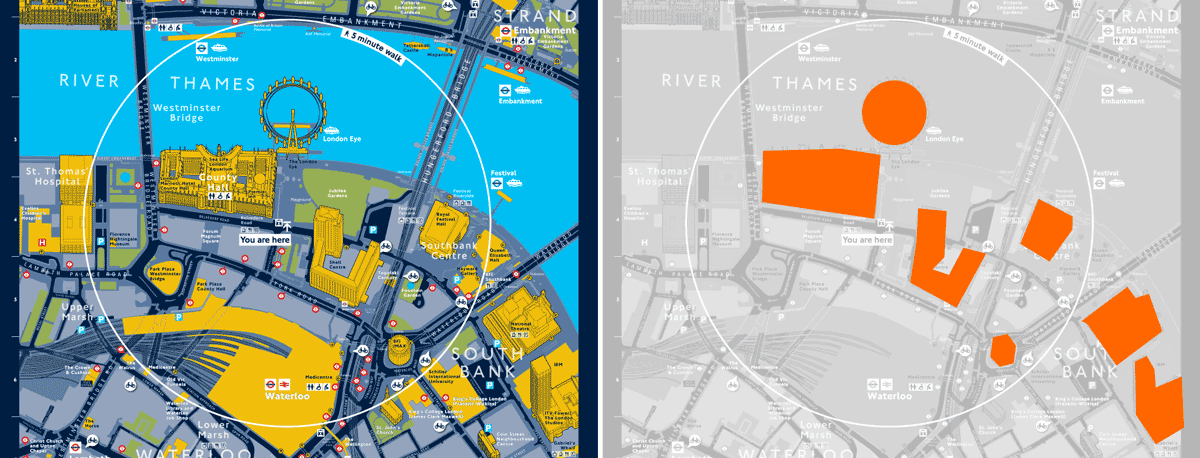

Legible London – London wayfinding

A landmark must have an element which singles it out from a host of other possibilities. The key physical characteristic is uniqueness or memorability. To be easily identifiable, it should have a clear form, contrasting with its surroundings, and some kind of spatial prominence. Careful, sparing selection of landmarks is essential in city wayfinding, with neither too many nor too few in use to allow only true landmarks to remain. These can vividly populate a user’s mental map of the city, and aid greatly to spatial awareness. Seen here on Legible London mapping.

Skilful employment of these elements not only reinforces the usefulness of a legible city wayfinding system, but also allows a city to flaunt specific aspects of its character, personality and uniqueness. And as Lynch proscribed, a city with a high imaginability will be legible, navigable, and enticing to its users.