A new study sheds light on the risk of letting people get by, using their phone to navigate rather than providing good wayfinding information. Sima Vaez is interested in the effect of urban form (urban street network and land use planning) on people’s wayfinding behaviour and the role of digital wayfinding on people’s social and spatial interactions. She compared wayfinding strategies based on mobile phone apps, finger-post signs and printed maps at Griffith University, Brisbane.

What Vaez found is a warning to cities who think the future of wayfinding lies in digital apps: they risk making us anti-social.

Wayfinding is important as it contributes to wellbeing and quality of life, while feeling lost is stressful. Studies show that people enjoy legible cities more and are more liable to come back, while a city which leads people to get lost leaves them unsatisfied. Wayfinding is also a social behaviour, in which we interact with others and plan similar routes.

The way visitors to a new city navigate in the digital era has been given less research attention than might be expected. Therefore Sima Vaez’ study examined differences in wayfinding strategies between three groups of participants who tested different navigational aids: one group used a paper map, a second used the Google Maps app, and the third group relied on local signage only. Data was collected during the survey by recording participants’ thoughts (think aloud survey), asking them to create a sketch map to show their aquired knowledge and follow-up interviews (including spatial recognition tests).

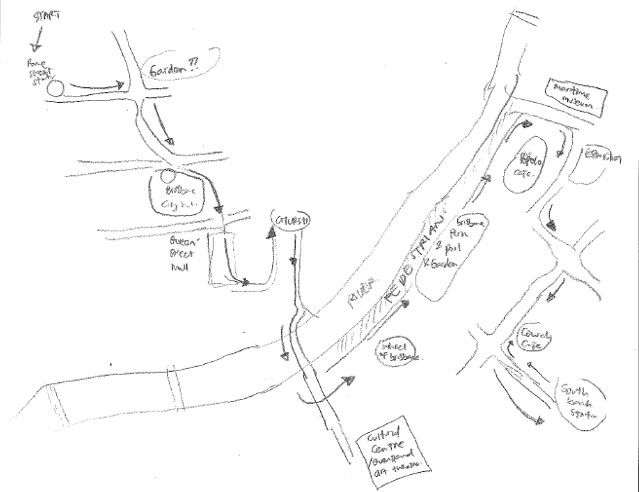

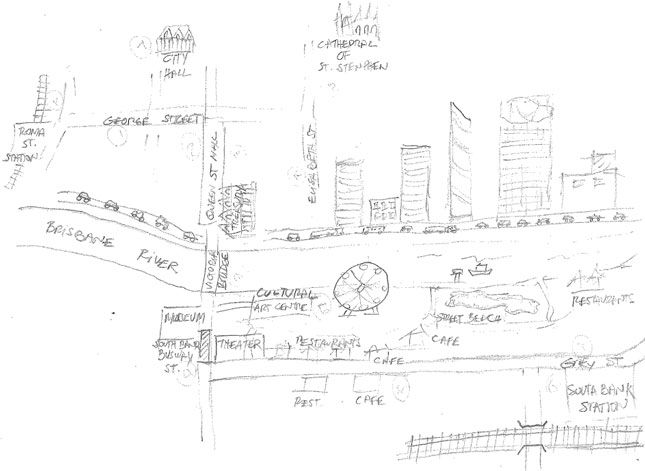

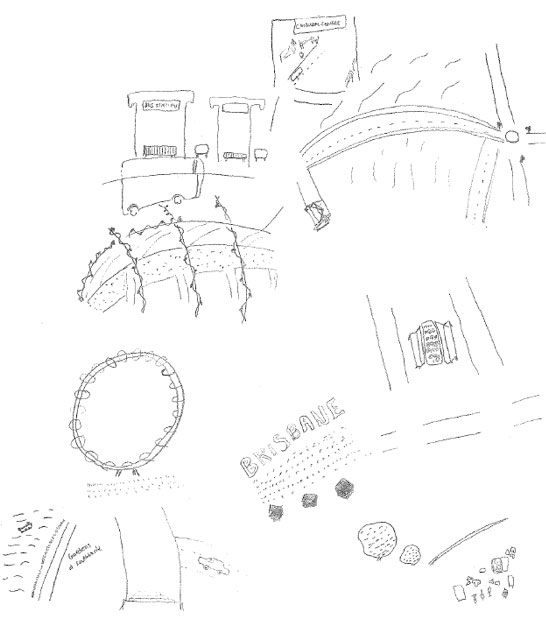

The sketch maps drawn on returning from the exercise illustrate a remarkable difference between the groups. The map and signage groups retained much more detail about their journey, noting street names, buildings, landmarks and cafes. Their sense of the surrounding area was more complete than the GPS group’s.

Vaez explains that the GPS group were simply not paying attention to their surroundings. They held previous expectations that they would be able to ‘follow the blue line’ to their destination and follow it back to the start. The other groups instinctively made mental notes of things they passed, probably so they were able to re-trace their steps. In this way hand held apps are disturbing our sense of orientation and navigation. GPS navigation is also responsible for disturbing ‘natural movement routes’. These routes are created as we strive to combine the fewest number of turns with highest level of visibility (keeping distant landmarks in view, for example).

The difference between the map and signage-only groups was more subtle. The signage group tended to notice the river, following it to locate the town centre, while the map group tended to plan their route to include a cafe and a well known square.

A more disturbing finding, according to Vaez, is that the GPS group displayed more anti-social behaviour. They chose to avoid crowds in order to interact with their device undisturbed. The other groups tended instead to flock towards other people, feeling safer when tending to move in a similar direction.

So what can cities learn from this research about how we navigate them?

Sima Vaez hopes that her research can improve our knowledge about how people way find so that we can improve the tools. She is convinced that if people find it easy to find their way then they will walk, cycle and use public transport but if they are unsure or feel lost, this will discourage them from these forms of mobility. Her research proved that GPS and digital aids can have a negative impact on our spacial cognition and knowledge of environment. This is something we must address when planning our cities.

So what are the trends? Are we moving inevitably towards a totally digital future?

“I don’t think so. Even people using GPS are still looking at the signage. They need confirmation. I am sure that we can never go the way of relying only on digital wayfinding tools.”